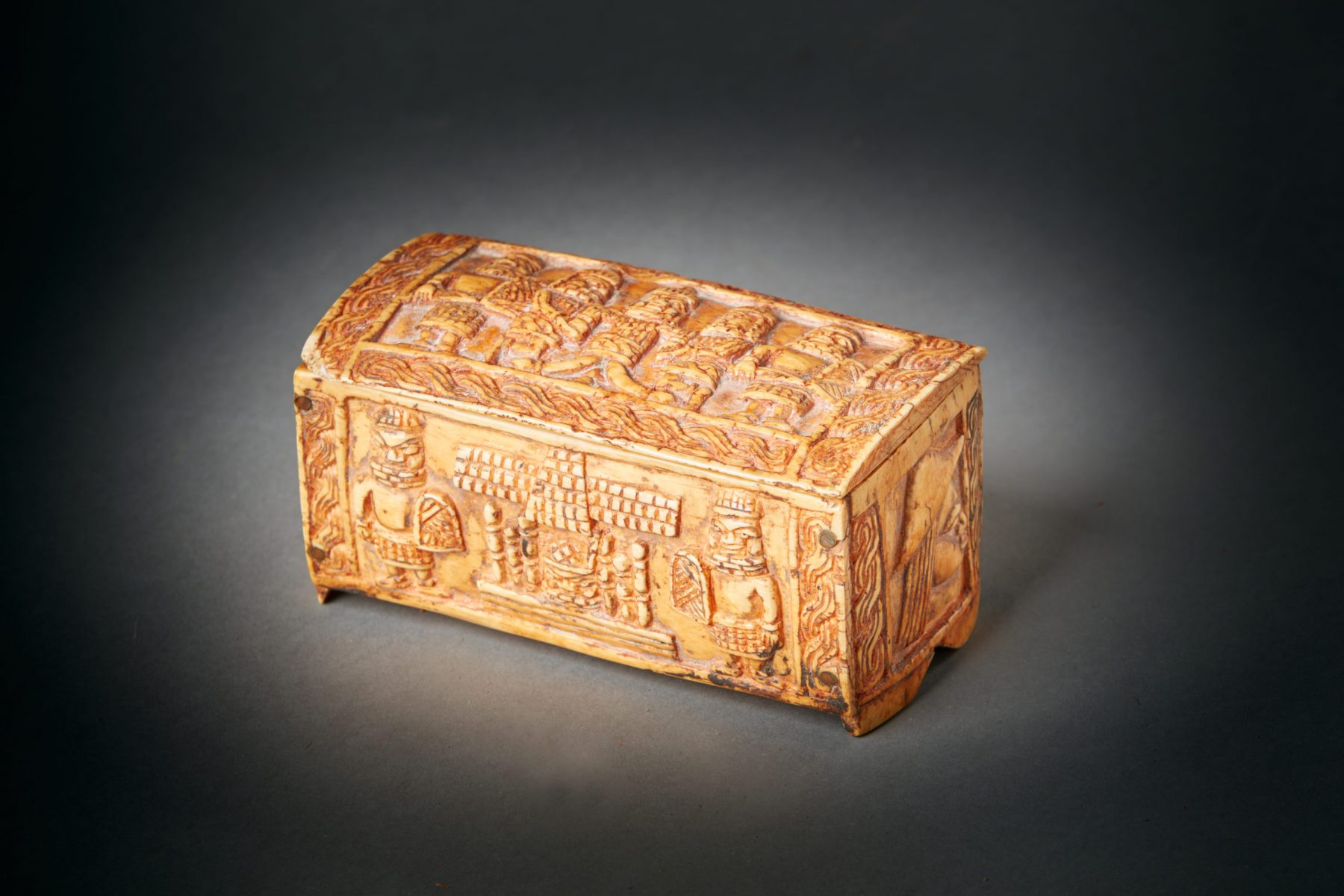

Benin Ivory Box Cirça 1650–1750 or early 18th century Ivory 6 x 3 x 3 in 15 x 8 x 8 cm Benin people; Nigeria, West Africa

Benin art served as both a sign of status and a record of court life. The Oba nobles, officials, and attendants were depicted on various objects, including bronze plaques. Costumes and regalia indicated their relative position in the court hierarchy. The warriors on these bronze plaques carry swords and short bows and wear headdresses or helmets embellished with imported horsetails. According to early accounts, horsetail headdresses symbolized military authority and were worn by war chiefs. Fanning out in low relief behind the heads, the horsetail is sculpted in a manner similar to Benin depictions of European hair or the fins and tails of the mudfish, a symbolically significant animal in Benin culture. Both Europeans and the mudfish are associated with Olokun, the god of the waters and bringer of wealth. Benin art emphasizes patterns and texture; empty space is avoided. A background pattern of quatrefoil "river leaves" is typical of most Benin bronze plaques. Symbolically the background design is another reference to Olokun, who is linked with the oba and wealth, and to the oba's monopoly on foreign trade. The kingdom of Benin offers a snapshot of a relatively well-organized and sophisticated African polity in operation before the major European colonial interlude.[2] Military operations relied on a well-trained disciplined force. At the head of the host stood the Oba of Benin. The monarch of the realm served as supreme military commander. Portuguese Influence The Portuguese first reached Benin, which they called Beny or Benin (although the Binis called themselves, their language, capital city, and their kingdom, EDO), during the reign of Ozolua between 1472 and 1486 AD. The Portuguese found a highly developed kingdom with unique and very sophisticated political, artistic, linguistic, economic, cultural, and military traditions in the process of territorial conquests. The Portuguese first explored the coast of Benin in 1472 but did not begin trading there until 1553. As the trade flourished, the Portuguese influence on Benin art became apparent. Traditional art began to incorporate European imagery. For example, because the Portuguese sailed into Africa with luxury items, Benin artists began to associate them with the Olokun, the god of seas and provider of earthly wealth. Images of the Portuguese sailors on bracelets, plaques, or masks came with images associated with Olokun such as crocodiles and pythons.[2] The brass plaque is also argued by historians to be a direct example of this Portuguese influence. There is an indication that the first appearance of the brass plaque came about during the period of Portuguese contact. It is argued that the plaques were inspired by picture books brought to Africa by the Portuguese sailors. This is evident in the fact that certain plaques come with designs that suggest Islamic or European influence.[2] Between 1504 and 1550 AD, the Portuguese, a major European power at the time, happily negotiated and established diplomatic and trade relations with Oba Esigie and his kingdom of Benin. Portuguese mercenaries fought alongside the Binis in many territorial wars after the treaty. Trade between the Portuguese and Benin was mainly in coral beads, cloths for ceremonial attire, and great quantities of brass manillas, which Bini craftsmen melted for casting. In exchange for Portuguese goods, the Binis offered tobacco, spices, cola nuts, ivory, earthenware, jewelry, artifacts, domestic slaves, etc. European slave trade in West Africa started with the acquisition of domestic servants, and warrior kingdoms like Edo had plenty of them captured as war booties. It was forbidden to sell or take a native Bini into slavery and so elaborate identification marks on faces and chests were contrived. Binis, therefore, were hardly ever captured by Arabs or Europeans and then forced or sold into slavery. One of the numerous elite palace associations was assigned the responsibility of conducting affairs with the Portuguese. Until this day, a secret language which some claim is derived from Portuguese is spoken by members of the association. Benin was the capital of the kingdom of Benin, which was probably founded in the 13th century and flourished from the 14th through the 17th century. The kingdom was ruled by the Oba and a sophisticated bureaucracy. From the late 15th century, Benin traded ivory, pepper, and cloth to Europeans. In the early 16th century, the Oba sent an ambassador to Lisbon, and the king of Portugal sent missionaries to Benin. After Benin was visited by the Portuguese in about 1485, historical Benin grew rich during the 16th and 17th centuries. In the early 16th century, the Oba sent an ambassador to Lisbon, and the King of Portugal sent Christian missionaries to Benin. As the trade flourished, the Portuguese influence on Benin art became apparent. Traditional art began to incorporate European imagery. For example, because the Portuguese sailed into Africa with luxury items, Benin artists began to associate them the Olokun, the god of seas and provider of earthly wealth. Images of the Portuguese sailors on bracelets, plaques or masks came with images associated with Olokun such as crocodiles and pythons.[2] The brass plaque is also argued by historians to be a direct example of this Portuguese influence. There is an indication that the first appearance of the brass plaque came about during the period of Portuguese contact. It is argued that the plaques were inspired by picture books brought to Africa by the Portuguese sailors. This is evident in the fact that certain plaques come with designs that suggest Islamic or European influence.[2] By the 15th century, the Edo tribes were a system of protected settlements that expanded into a thriving city-state. During this time, the twelfth Oba in line was Oba Ewuare the Great (1440–1473) who would expand the city-state to an empire. It was not until the 15th century, during the reign of Oba Ewuare the Great, that the kingdom's administrative center, the city Ubinu, began to be known as "Benin City" by the Portuguese and would later be adopted by the locals as well. Before then, due to the pronounced ethnic diversity at the kingdom's headquarters during the 15th century from the successes of Oba Ewuare, the earlier name ('Ubinu') by a tribe of the Edos was colloquially spoken as "Bini" by the mix of Itsekiri, Edo, Urhobo living together in the royal administrative center of the kingdom. The Portuguese would write this down as Benin City. Though, farther Edo clans, such as the Itsekiris and the Urhobos, still referred to the city as Ubini until the late 19th century, as evidence implies. About 36 known Ogiso are accounted for as rulers of the Benin Empire. According to the Edo oral tradition, during the reign of the last Ogiso, his son and heir apparent, Ekaladerhan, was banished from Igodomigodo (modern-day "Benin Empire 1180-1897") as a result of one of the Queens having deliberately changed an oracle message to the Ogiso. Prince Ekaladerhan was a powerful warrior and well-loved. On leaving Benin, he traveled in a westerly direction to the land of the Yoruba. The Yoruba were well known beyond Africa by Arabic and Greek scholars as a unique civilization whose influence, wisdom, and religion attracted envy and persecution. At that time, according to the Yoruba, the Ifá oracle said that the Yoruba people of Ile Ife (also known as Ife) would be ruled by a man who would demonstrate his proof of birth and relation to Ile-Ife. Ekaladerhan's arrival at the Yoruba city of Ife was never known or told as oral history anywhere until revisionists' spin that he changed his name to Izoduwa (which in his native language meant 'I have chosen the path of prosperity') and became The Great Oduduwa, also known as Oduduwa, Oòdua, of the Yoruba. After the death of his father, the last Ogiso, a group of Benin chiefs led by Chief Oliha came to Ife, pleading with Oduduwa (the Ooni) to return to Igodomigodo (later known as Benin City in the 15th century during Oba Ewuare) to ascend the throne. Oduduwa's reply was that a ruler could not leave his domain, but he had seven sons and would ask one of them to go back to become the next king there. However, Yoruba's real Oduduwa existed centuries before Jesus Christ or Mohammed. There are other versions of the story of Oduduwa. Many Yoruba often regard Oduduwa as a god/mystery spirit or prince coming from a place towards the east of the land of the Yoruba people. Though this would rudimentarily seem to confirm the Bini spin on his history due to the fact that Benin is technically to the east of Ife, his origin tends not to be attributed to Benin City. If everyone that came from the east was Oduduwa, so were the Urhobo, Igbo, and Efik Oduduwa. Eweka I was the first 'Oba' or king of the new dynasty after the end of the era of Ogiso. He changed the ancient name of Igodomigodo to Edo. Centuries later, in 1440, Oba Ewuare, also known as Ewuare the Great, came to power and turned the city-state into an empire. It was only at this time that the administrative centre of the kingdom began to be referred to as Ubinu after the Itsekhiri word and corrupted to Bini by the Itsekhiri, Edo, Urhobo, Ijaw, and Calabar living together in the royal administrative center of the kingdom. The Portuguese who arrived in 1485 would refer to it as Benin and the center would become known as Benin City and its empire Benin Empire. The ancient Benin Empire, as with the Oyo Empire, which eventually gained political ascendancy over even Ile-Ife, gained political strength and ascendancy over much of what is now Midwestern and Western Nigeria, with the Oyo Empire bordering it on the west, the Niger river on the east, and the northerly lands succumbing to Fulani Muslim invasion in the North. Interestingly, much of what is now known as Western Iboland and even Yoruba Land was conquered by the Benin Kingdom in the late 19th century—Agbor (Ika), Akure, Owo, and even the present day Lagos Island, which was named "Eko" meaning "War Camp" by the Bini. 17th Century The 17th century witnessed another period of internal turmoil in Benin history. After the death of Ehengbuda, the last warrior king in the late 16th century AD, his son Ohuan ascended the throne, but he did not reign for long, and he produced no heir. With his death, the lineage that produced the Eweka dynasty ended. Powerful rebel chiefs established private bases and selected kings from among their ranks. This produced a series of kings with doubtful claims to legitimacy, which seriously weakened the Benin monarchy. At the turn of the 17th century, a very powerful Iyase (head of chiefs and the supreme military commander of the kingdom), rebelled against Oba Ewuakpe and after Oba's death, supported a rival brother to the heir apparent, who won and became Akenzua I. This rebel (the Iyase ne Ode), is remembered in Benin oral history as a threatening foe and a powerful magician who could transform himself into an elephant at will. Oba Akenzua I, from 1715 AD and Oba Eresonyen from 1735 AD, successfully fought the rebellious chiefs and restored power and legitimacy to the Bini monarchy. Their reigns were followed by that of Akengbuda in 1750, by Obanosa and Ogbebo in quick succession in 1804, by Osemwede in 1815, and by Oba Adolo in 1850. Provenance: Within the past sixty years or so, the ivory box was collected by a private French collector during the 1940s and later ended up in several German collections ultimately ending up in the Ex- private collection of Madame Georgia Chrischilles, president of the BOA; Brussels Oriental Art Fair (BOA), and later being sold. Exhibited by Bernard de Grunne; Parcours des mondes, Paris France. The approximate age of the manufacturing of this exquisitely carved ivory box artifact was determined to be around the King Oba regimes that might be responsible for consigning its production. The following chronological list of King Oba’s regimes from the beginning of the ancient Benin Empires until during the Pitt Rivers punitive expeditions period of 1897 includes the earliest known historical encounters with Europeans and the Portuguese merchant marines. This brief historical scenario supplies historical context of what might have been happening politically during this period of the Benin societies such as trade and commerce with the Europeans namely the Portuguese merchant marines which first embarked on trade with the Benin Empire as early as the 15th century. Thus the following research has been compiled and composed from hundreds of archives.